Published on Spare Change News, Feb. 2015

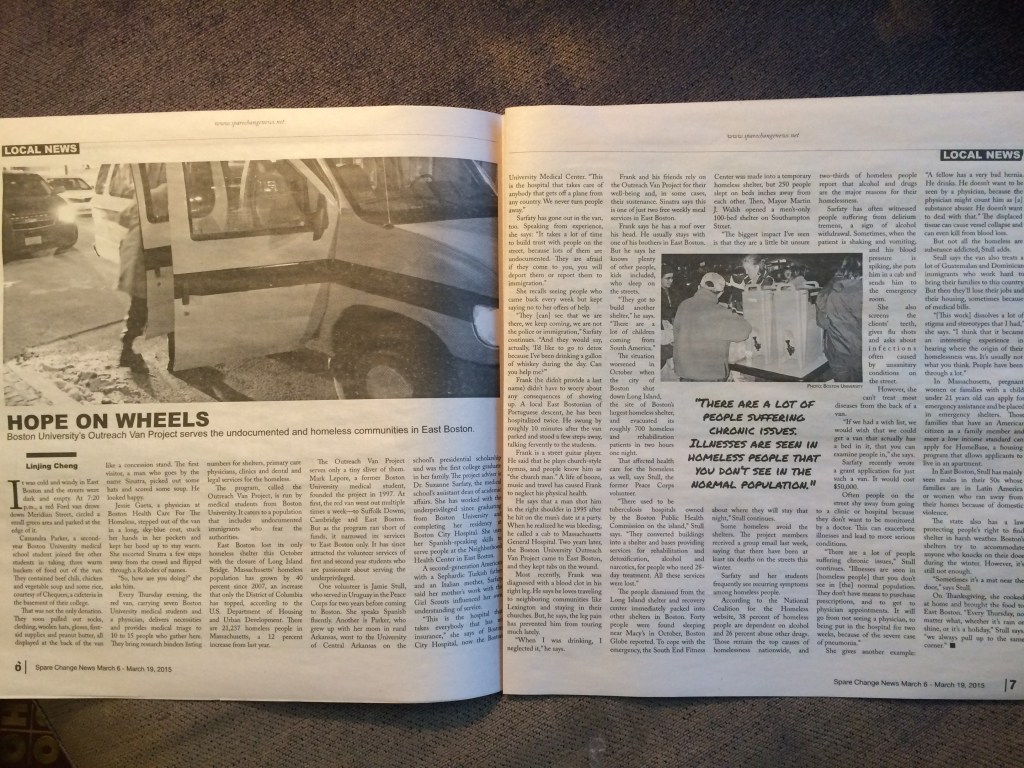

It was cold and windy in East Boston on the first Thursday of December, its Central Square dark and largely empty. A red Ford E350 drove down Meridian Street, circled a strip of green field about 7:20 in the evening and pulled alongside its edge.

Cassandra Parker, a second-year Boston University medical school student joined five other students in moving three warm buckets of food out of the car. They contained beef chili, chicken soup, vegetable soup and some rice, courtesy of Chequers, a cafeteria in the basement of their school.

That was not the only donation. Soon, they drew out socks, clothing, woolen hats, gloves, first aid supplies and peanut butter, displayed at the back of the van like a concession stand at a state fair. The first visitor, a man who said that he goes by Sinatra, picked out some hats and scooped some soup, a happy expression on his face.

Jessie Gaeta, a physician at Boston Health Care for The Homeless, stepped out of the van in her long, sky-blue coat, sticking her hands in the pockets and her head in a hoodie to keep warm. She escorted Sinatra a few steps away from the crowd, flipping through a Rolodex of names.

“So how are you doing?” she asked him.

Every Thursday evening, the red van, carrying seven BU medical school students and a physician, delivers necessities and provides medical triage to 10 to 15 people who gather here. They also bring research binders listing numbers for shelters, primary care physicians, clinics, dental and legal services for homeless.

The program, Outreach Van Project, is run by medical students from Boston University. It caters to a population that includes undocumented immigrants who fear authorities.

East Boston lost its only homeless shelter this October with the shutdown of Long Island Bridge. Statewide, Massachusetts homeless population has grown by 40 percent since 2007, a percentage increase topped nationwide only by the District of Columbia, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. There are 21,237 homeless people in Massachusetts, a 12 percent increase from last year.

The Outreach Van serves but a tiny sliver of them. Mark Lepore, a student in the class of 1999, founded the project in 1997. The red van then went out multiple times a week to the horse track at Suffolk Downs, to Cambridge and to East Boston. But as the program ran short of funds, it narrowed the service to East Boston. As “staff,” it has since attracted first and second year students who feel strongly about the underprivileged.

One volunteer is Jamie Stull, who served in Uruguay in the Peace Corps for two years before coming to BU and speaks Spanish fluently. Another is Cassandra Parker, who grew up with her mom in a rural Arkansas, went to University of Central Arkansas on the school’s presidential scholarship, and was the first college graduate in her family. The project adviser is Dr. Suzanne Sarfaty, the medical school’s Assistant Dean of Academic Affairs. She has worked with the underprivileged since she graduated from BU, completing her residency at Boston City Hospital and using her Spanish skills to serve people at the Neighborhood Health Center in East Boston.

A Second generation American with a Sephardic Turkish father and an Italian mother, Sarfaty said her mom’s service to the Girl Scouts influenced her sense of service.

“This is the hospital that takes everybody that has no insurance,” she says of Boston City Hospital, now, the BU Medical Center. This is the hospital that takes care of anybody that gets off a plane from any country. We never turn people away.”

She has gone out on the van as well. Speaking from experience, she said, “It takes a lot of time to build trust with people on the street, because lots of them are undocumented. They are afraid if they come to you, you will deport them or report them to immigration.”

She recalled seeing some people who would come back every week, but kept saying no to her offers of help.

“On the sixth week, they [could] see that we are there, we keep coming, we are not the police or immigration. And they would say, actually, ‘I’d like to go to Detox, because I’ve been drinking a gallon whiskey during the day. Can you help me?’”

The story of one client

Frank (he didn’t provide a last name) didn’t have to worry about showing up. A local East Bostonian of Portuguese descent, he has been hospitalized twice. He swung by roughly 10 minutes after the van parked, and stood a few steps away, talking fervently to the students.

Frank is a street guitar player. He said that he plays church-style hymns, and people know him as “the church man.” The lifestyle of booze, music and travel, has caused Frank to neglect his physical pains. At least when he can.

Frank recounted that a guy shot him in the right shoulder,in 1995, after he hit on the man’s date at a party. When he realized he was bleeding, he called a cab to Mass General Hospital. Two years later, the BU Outreach Van Project came to East Boston, and it kept tabs on his wound.

Most recently, Frank was diagnosed with a blood clot in his right leg. He said he loves traveling to neighboring communities, like Lexington, and staying in their churches. But, he says, the leg pain has prevented him from touring much lately.

“When I was drinking, I neglected it,” he said.

Frank and his friends rely on Outreach Van Project for their well-being and in some cases sustenance. Sinatra says this is one of just two free weekly meal services in East Boston.

Frank says he has a roof over his head. He usually stays with one of his brothers in East Boston. But he says he knows plenty of other people, kids included, who sleep on the streets.

“They got to build another shelter,” he says. “There are a lot of children coming from South America.”

The situation got worse in October when the city of Boston shut down Long Island Bridge, Boston’s largest homeless shelter, and evacuated its roughly 700 homeless and rehabilitation patients in two hours one night.

That, says Stull, the former Peace Corps volunteer, affected health care for the homeless as well.

“There used to be tuberculosis hospitals owned by the Boston Public Health Commission on the island,” Stull said, “They converted buildings into a shelter, and bases providing services for rehabilitation and detoxification, alcohol and narcotics, for people who need 28-day-treatment. All these services were lost.”

The people dismissed from Long Island shelter and recovery center immediately packed other shelters in Boston. Forty people were found sleeping near Macy’s in October, The Boston Globe reported. To cope with the emergency, the South End Fitness Center was made into a temporary homeless shelter, but 250 slept on beds that are inches away from each other.

Said Stull, “The biggest impact I’ve seen is that they are a little bit unsure about where they will stay that night.”

Some homeless avoid the shelters. The project members received a group email last week, saying that there have been at least six deaths on the street this winter.

The burden of life on the street

Sarfaty and her students see some of the same symptoms frequently among homeless people.

According to nationalhomeless.org, 38 percent of homeless people are dependent on alcohol and 26 percent abuse other drugs. Those remain the top causes of homelessness nationwide: two-thirds of homeless people report that alcohol and drug were major reasons.

She has often seen delirium tremors, a sign of alcohol withdrawal. Sometimes when the patient is shaking and vomiting, his blood pressure spiking, she puts him in a cab to an emergency room.

She also screens the clients’ teeth, gives flu shots and asks about infections often caused by unsanitary conditions on the street.

However, she can’t treat most diseases from the back of a van.

“If we had a wish list, we would wish that we could get a van that actually has a bed in it, that you can examine people.” she said.

Sarfaty recently wrote a grant application for just such a van. It would cost $50,000.

Often people on the street shy away from going to a clinic or hospital because they don’t want to be monitored by a doctor. This can compound illnesses, making the more serious.

“There are a lot of people suffering chronic issues,” Stull said. “Illnesses are seen in them that you don’t see in normal population. They don’t have means to purchase prescriptions, and to get to physician appointments. It will go from not seeing physician, to being put in hospital for two weeks, because of the severe case of pneumonia.”

She gave another example. “A fellow has a very bad hernia. He drinks. He doesn’t want to be seen by a physician, because the physician might count him as substance abuser. He doesn’t want to deal with that.” The displaced tissue can cause vessel collapse and kill him from blood loss.

But not all the homeless are substance addicted, Stull says.

Stull says the van also sees lots of Guatemalan and Dominican immigrants who work hard to get their families to this country. But then they’ll lose their jobs and their housing, sometimes because of big medical bills.

“[This work] dissolves a lot of stigma and stereotypes that I had,” she said. “I think that it became an interesting experience in hearing where the origin of their homelessness were. It’s usually not what you think. People have been through a lot.”

In Massachusetts, families with a child under 21 years old, or pregnant women can apply for Emergency Assistance, and are placed in emergency shelters. Those families that have an American citizen as a family member and meet a low income standards can apply for HomeBase, a housing program that allows applicants to live in an apartment.

What Stull has seen in East Boston is mostly males in their 50s, whose families are in Latin America, or women who ran away from homes because of domestic violence.

The state also has a law protecting people’s rights to find shelter in the harsh weather. Boston’s shelters try to accommodate everyone who knocks on their doors during the winter.

Still, Stull said, “Sometimes it’s a mat near the door.”

On Thanksgiving, she cooked at home and brought the food to East Boston.

“Every Thursday, no matter what, whether it’s rain or shine, or it’s a holiday,” she said, “we always pull up to the same corner.”

留下评论